The last few years have been characterised by a deep crisis that seems paradoxical, as the world is modernising and the knowledge industry is evolving positively. However, from this experience, one question has emerged, raising a simple yet urgent issue: Do think tanks (TTs) still possess the institutional building blocks to deliver credible and sustained policy influence?

Drawing on the State of the Sector Survey 2025 (which surveyed 44 think tanks in the sub-region) and ACED’s on-the-ground experience, we aim to share insights with actors working to catalyse development by supporting and strengthening “think tanking¹.”

Download the On Think Tanks State of the Sector Report 2025

1. Where are the biggest skills gaps?

Someone says, “a man, a goal and the means”. Here we might say, “an organisation, a goal and the means”. Whatever the context, it is the means that make the difference. They are the driver that enables a think tank to move confidently toward its goals.

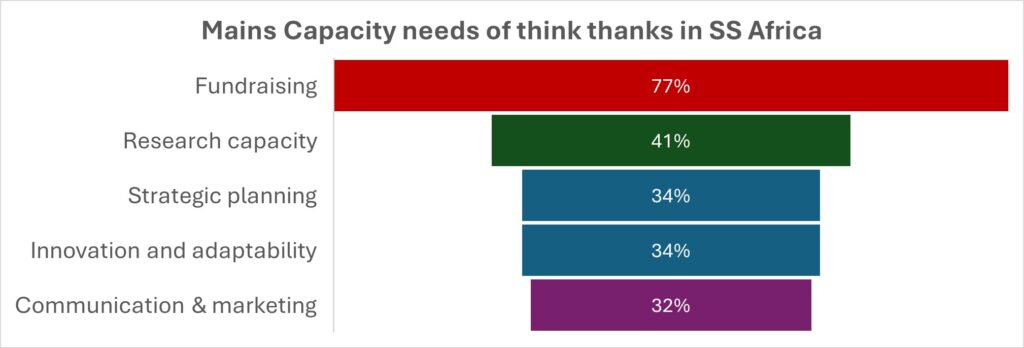

But what do think tanks themselves say they need to get stronger? When asked to choose up to three priority areas, respondents highlighted the following themes (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Mains Capacity needs of think tanks in SS Africa

There’s a critical paradox here: even though fundraising is the most widely cited need, many organisations still underinvest in it. Only 41% report dedicating a moderate share of resources to fundraising, while 36% of budgets go to communications. In short, think tanks want better funding but often don’t treat fundraising as a strategic, core function that requires professional investment. Furthermore, for some organisations, visibility itself is seen as a key factor of affirmation within their ecosystem—a way to prove relevance and strengthen their position, even when their financial base remains fragile.

2. Is AI a help or another challenge?

Technology has become impossible to ignore, and artificial intelligence is no exception. More than half (57%) of the surveyed think tanks already use AI tools, but mostly in fundamental ways, such as routine tasks like grammar correction (50%) and meeting note-taking (34%). Advanced uses, such as chatbots, image or video generation, and coding, remain rare (30% and 23%, respectively).

So AI is already reshaping expectations. As one leader put it, “Today we can’t admit that someone writes a text with mistakes.” Yet, without intentional investments in skills and governance, AI risks widening gaps rather than closing them, as barriers still hinder its use. Survey data for sub-Saharan think tanks show that barriers to broader adoption are practical and ethical:

- Lack of expertise (20%),

- ethical concerns (16%),

- and infrastructure limits (16%).

Just as importantly, think tank staff themselves are clear about what they need to make AI truly useful. Their top skill needs are below in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Skills needed by Sub-Saharan African think tanks to use AI effectively

3. If think tanks could set their own agenda, what would they focus on?

In a quest for autonomy, TT could set up the agenda independently. The response below is the answers to the question ‘’If local think tanks could independently set the agenda, what would be the top 3 issues that think tanks … should focus their attention on.

Survey respondents prioritise systemic national challenges: economics (82%), governance (64%), peace & security (48%), education (41%), and environment & climate (41%). This demonstrates ambition: local actors aim to work on large, systemic issues that impact citizens’ lives. At the same time, it is important to underline that other social concerns, such as public health and food security, and other cross-cutting themes, also deserve attention.

4. What discussions do we have on building blocks and what matters?

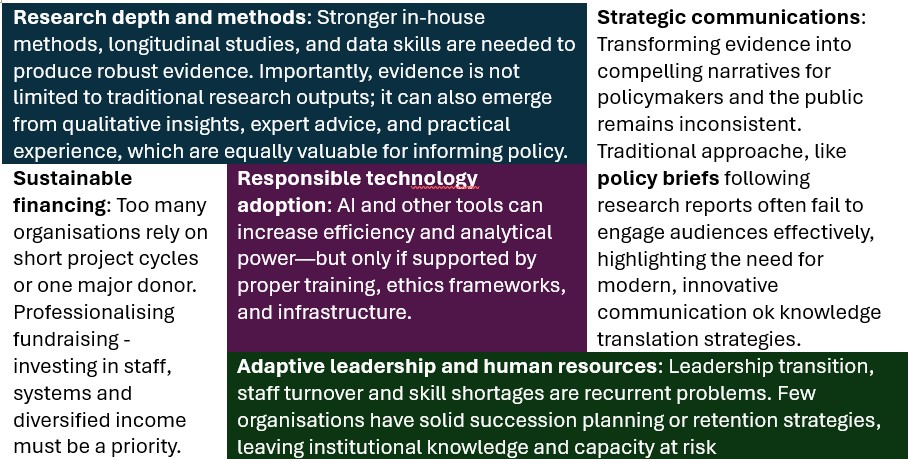

The survey and field experience point to a set of core institutional deficits that limit think tanks’ long-term impact:

5. How should funders and supporting organisations respond?

Will funders continue to treat think tanks like short-term contractors, or will they invest in their long-term foundations? If funders want to achieve durable policy influence, the answer is clear: fund institutions, not just projects. Encouragingly, some donors are already shifting course, offering more flexible support that helps think tanks adapt to their environment. But much more is needed.

Concrete steps to back that shift:

- Offer multi-year core and flexible funding that enables long-term research agendas, staff retention and organisational learning.

- Invest in fundraising capacity: support professional development for resource mobilisation and provide matched-funding mechanisms to incentivise local income.

- Back leadership development and HR systems: succession planning, competitive pay, and professional HR practices reduce institutional risk.

- Support data and AI literacy at scale: trainings in data analysis, visualisation, and AI governance; resources for ethical AI use and investments in basic IT infrastructure.

- Fund communications and knowledge translation as a strategic function, not a side project—media strategy, policy engagement teams, and innovative tools like structured dialogue spaces and digital outreach amplify evidence and impact.

A final call: Invest in think tank foundations, not just outputs

Think tanks play a central role in building resilient, evidence-based policymaking in Sub-Saharan Africa. Yet their credibility and influence depend not only on producing clever reports but on the strength of their institutions. Durable financing, skilled teams, ethical use of technology, and effective communication are the proper foundations of long-term impact.

If we want African think tanks to keep “thinking” and shaping the continent’s future, donors and partners must move beyond episodic project grants. The priority now is long-term, flexible support that strengthens institutions from within.

For funders ready to act, the opportunity is clear and urgent: by backing fundraising systems, deeper research capacity, adaptive leadership, and responsible AI adoption, partners can help build think tanks that thrive—not just survive. The payoff is immense: better policy, stronger civic dialogue, and more resilient societies across Africa.

1. “Think tanking” isn’t a formal academic term, but it’s increasingly used in practice to describe the whole ecosystem of producing, translating, and using evidence for policy influence