When a major donor suddenly exits, the shockwaves don’t spread evenly. Our analysis of USAID’s withdrawal shows that while most think tanks reported little to no impact, the effects were concentrated in specific regions and themes. Conversations in India highlight a parallel story: resilience is being tested as foreign funding shrinks, corporate giving rises, and new philanthropists emerge and reshape the ecosystem.

A mixed picture of resilience

USAID’s abrupt exit, when the U.S. Government cancelled most programmes and contracts, raised a pressing question: what happens when external funding disappears overnight?

Our survey data suggests that most organisations were insulated:

- 73% reported no impact or very little impact

- 14% reported being very or very much affected

- 13% described the impact as moderate

Download the On Think Tanks State of the Sector Report 2025

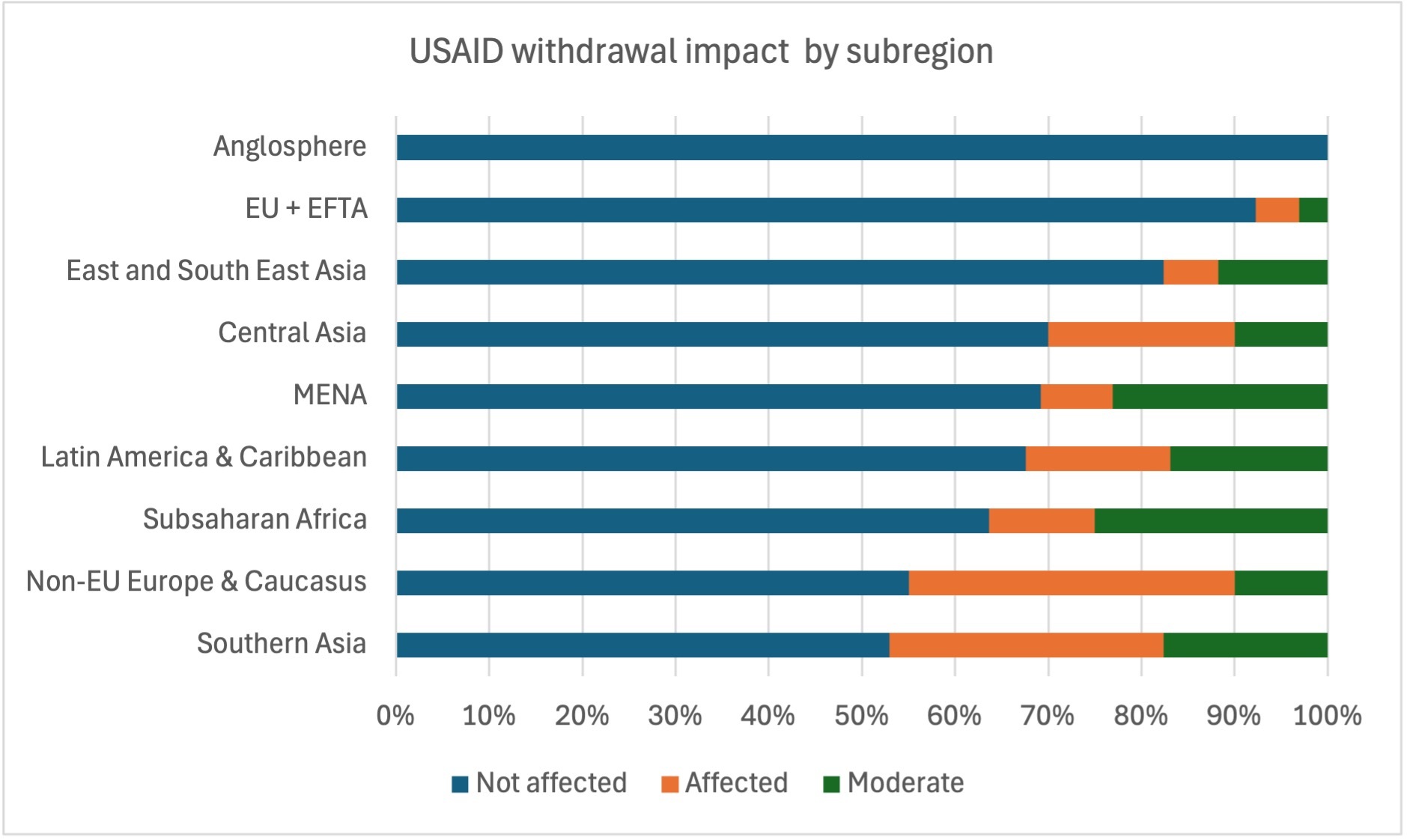

The impact was not evenly distributed across regions. The sharpest disruptions were felt in Non-EU Europe & the Caucasus, where U.S. funding had historically underpinned organisations working on governance, democratic institutions, and human rights. These are areas where domestic philanthropy is often limited, making international support indispensable.

A second cluster of impact emerged in Southern Asia, where reliance on international funding is high and domestic sources have been slower to step in. Yet, within this region, the picture is more complex. India, for example, was not significantly affected by USAID’s cuts. Conversations with funders and think tanks suggest this is because USAID’s footprint in India had already been declining, and the real shock to Indian organisations came from the recent tightening of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act (FCRA) implementation. Enacted in 1976 and significantly amended in 2010 and 2020, the FCRA is the central law governing how Indian organisations receive and utilise foreign funding. Its stated purpose is to ensure that foreign contributions do not undermine national interest or political processes. In practice, however, successive rounds of amendments have introduced stringent registration requirements, capped administrative expenses, restricted sub-granting, and increased government scrutiny. These measures have severely curtailed international inflows to Indian non-profits, making the regulatory regime a far greater constraint than the gradual decline of USAID’s programme presence.

Instead of USAID’s exit, Indian organisations are navigating a structural shift

India has a rich and complex history of civil society organisations (CSOs) and think tanks shaping debates on policy, governance, and social change. This tradition is rooted, in part, in deeply ingrained customs and practices of altruistic philanthropy, driven by both religious and social motivations. Their ability to thrive has long depended on the mix of domestic and international funding available. As foreign contributions have become increasingly difficult to access, most notably with the recent FCRA amendments, the role of domestic philanthropy has become more prominent. Yet, conversations with funders and organisations alike reveal that while this shift has opened up new opportunities, it has also introduced fresh constraints that affect the independence, scope, and sustainability of CSOs and think tanks.

- Domestic philanthropy, championed by Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (UHNWIs), is growing rapidly but tends to prioritise “safe” sectors, such as education and health, over politically sensitive themes, including governance and rights.

- CSR funding plays a crucial role in supporting a diverse range of initiatives. It is often structured around shorter grant cycles, typically one year, with a strong emphasis on measurable, visible outcomes. In many cases, considerations such as brand reputation and public visibility are also important drivers of CSR strategies.

- Domestic philanthropists and intermediaries are experimenting with seed/core support and collaborative models, but these remain the exception rather than the rule.

- International donors previously offered substantial core support (sometimes more than half of budgets). In contrast, domestic donors typically cap core at 10% or less, pushing organisations into projectised models that weaken long-term influence.

- Some organisations have shifted to alternative structures (e.g., for-profit registration) to reduce compliance risks, but this raises sustainability questions.

- Funders, particularly corporates, often emphasise quantifiable, short-term results, which can sometimes be at odds with the longer time horizons required for policy change or systemic reform.

- A new wave of domestic wealth beyond major metropolitan areas is entering philanthropy, but many new donors are risk-averse and lack familiarity with strategic giving.

- Donor motivations remain mixed: some are beginning to prioritise evidence and data, while others still rely on emotional or traditional drivers, making patient capital scarce.

Thematic vulnerability matters more than size

To better understand which organisations felt the strongest impact from USAID’s exit, we analysed responses by organisational size, budget, thematic focus, and donor diversification. Interestingly, neither organisational size (measured by staff count) nor budget level (measured by turnover) showed a statistically significant relationship with the reported impact. Larger organisations were not inherently more resilient, and smaller ones were not necessarily more exposed.

Instead, thematic focus emerged as the decisive factor. The probability of being affected was notably higher for think tanks working on gender, governance, justice, peace, and security, while those focused on technology reported far lower levels of disruption. These differences were statistically significant and reflect USAID’s historical funding priorities, which include a strong emphasis on democratic governance, peacebuilding, and gender equity, with relatively limited investment in technology policy.

Insights from India reinforce this finding but also highlight how vulnerability plays out differently depending on the funding ecosystem. In India, USAID’s withdrawal itself did not register strongly, but organisations working on politically sensitive areas, such as governance and rights, have faced acute funding challenges because domestic donors remain hesitant to support them. By contrast, “safe” sectors such as education, health, and livelihoods continue to attract substantial CSR and philanthropic funds, even as foreign inflows have dried up.

This suggests that thematic vulnerability is not just about the exit of a single donor, but about whether alternative funding ecosystems are willing to support critical but sensitive areas of work. Where local philanthropy is cautious, as in India, exits can deepen gaps in precisely those domains most vital for long-term democratic resilience.

Funding diversification

Interestingly, the share of an organisation’s budget coming from a single donor does not show a statistically significant relationship with the level of impact reported. At first glance, it might be expected that highly donor-dependent think tanks would be the most vulnerable to USAID’s exit. Indeed, organisations that relied heavily on one funder did report stronger effects, especially those indicating they were “very much” affected. But these differences were not robust enough to be statistically confirmed.

This finding highlights an important point: donor dependency alone does not fully explain vulnerability. The data suggests that what matters more is thematic exposure, whether an organisation operates in fields historically prioritised by USAID, such as governance, peace, or gender equity, where the withdrawal of a single major backer can leave a deeper gap.

Insights from India help illustrate this nuance. Many Indian think tanks already had to adapt to a funding environment where foreign support collapsed due to FCRA restrictions, not just the exit of one donor. Those with diverse portfolios still found themselves squeezed if they worked on politically sensitive themes, such as accountability or rights, where domestic philanthropy and CSR funds are hesitant to step in. Conversely, organisations focused on “safe” sectors such as education, health, or livelihoods continued to secure support, even when their donor bases were relatively narrow.

Lessons for resilience

In conclusion, the resilience of think tanks depends not merely on the breadth of their donor base but also on the readiness of funders to engage with the issues at stake. A wide portfolio of supporters may provide some stability, but without genuine thematic alignment, this diversity can prove fragile. Where domestic funders remain hesitant to support politically sensitive or less visible areas, even well-diversified organisations may struggle to withstand the exit of a major international donor. Ensuring resilience, therefore, is as much about building shared commitment as it is about expanding the pool of supporters.