About this report

This report was prepared by Madinah Institute (MI), using survey data provided by On Think Tanks (OTT), as one of a series of local reports accompanying the global “Think Tank State of the Sector 2025” report. It offers insights into think tanks in Saudi Arabia, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region, and the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA), focusing on four key dimensions: Funding, Staffing, Impact Measurement, and Digital Strategy. We benchmark regional findings against global survey data (335 think tanks worldwide). All figures are percentages of survey respondents unless mentioned. Key visualisations (bar charts, heat maps, radar graphs) are included to compare regions, and we conclude with actionable recommendations.

Download the On Think Tanks State of the Sector Report 2025

Executive Summary

This report, prepared by the Madinah Institute with survey data from On Think Tanks (OTT), examines the state of think tanks in Saudi Arabia, the GCC, and MENA, benchmarking them against global peers (335 think tanks worldwide). It covers funding, staffing, impact measurement, and digital strategy, highlighting both the strengths and challenges.

Funding:

Think tanks in the GCC rely heavily on government and foundation core funding (75% vs. 23% globally), ensuring stability but creating sustainability risks if priorities shift. Budgets are steady or growing, with most grants spanning one to four years.

Staffing:

Most institutions are small (under 20 staff) yet optimistic about hiring (77% plan growth). Teams are young (half under 35), digitally skilled, and largely on secure contracts. Challenges include a shortage of senior experts and competition from academia/government.

Impact:

Influence is primarily measured by media visibility and policy engagement. Around 62% contributed to policy in the last five years. Outputs are diverse—reports, events, and digital content—though credibility often ties to national visions , such as Vision 2030.

Digital Strategy:

Most have communications teams (85%) and allocate ~15% of budgets to outreach. Social media use is widespread, but AI adoption is negligible in the GCC (0%), unlike in the broader MENA region. Barriers include ethics and resistance to change.

Recommendations:

- Diversify funding to reduce dependence.

- Invest in staff training and fellowships.

- Strengthen impact measurement.

- Adopt AI and digital tools gradually, under ethical frameworks.

Funding Landscape (Saudi Arabia, GCC, MENA vs Global)

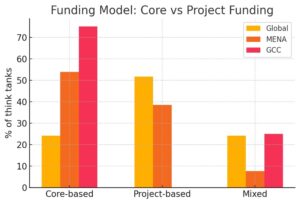

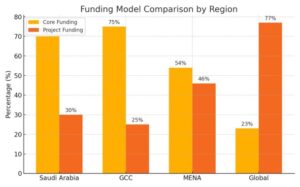

Reliance on Core Funding vs. Project Funding: Think tanks in the MENA region – and especially those in the GCC – rely far more on core funding than their global peers. Over half of MENA think tanks (54%) report that their funding is primarily core/unrestricted (e.g. institutional grants covering operational costs), whereas globally only 23% are mostly core-funded. In contrast, just 38% of MENA institutes rely mainly on project-based funding, compared to about 51% globally. The difference is even starker in the GCC: 75% of GCC think tanks are core-funded and none are primarily project-funded, versus 50% globally (see Figure 1). By comparison, Saudi respondents (all three in the sample) were either core-funded or had mixed funding – none relied mostly on projects.

Figure 1: Funding models – Share of think tanks primarily core-funded vs project-funded. GCC think tanks stand out with about 75% core-funded, far above the global average. (Source: OTT SOS 2025 survey)

This heavy core funding in GCC likely reflects government or endowment support. Indeed, 100% of GCC think tanks surveyed cited government grants as a top funding source, and 50% cited domestic foundations, while none selected international donors. In the MENA sample, funding sources were more diversified, with approximately 38% each named as government, international development agencies, and corporations among the top funders. Still, local funding dominates; international donor funding was mentioned by only 5 of the 13 MENA think tanks (38%), compared to 50% globally. This suggests GCC institutes are government-supported, whereas MENA think tanks outside the Gulf are a mix of government, foreign, and private funding. Globally, by contrast, the most common funders are international development partners (e.g., USAID, UN) and foundations, followed by governments.

Funding Duration and Stability: MENA funding appears somewhat more stable and longer-term than in other regions. None of the MENA respondents reported typically receiving funding under 6 months, whereas 15% globally had sub-6-month funding cycles. In fact, 85% of MENA think tanks have typical grants or contracts lasting 1–4 years (with 38% at 2–4 years), which is longer than the global norm (the most common duration globally is 1–2 years). Correspondingly, MENA think tanks were less likely to report funding decreases in the past year. Only 1 of 13 MENA think tanks saw funding drop in the last year, while 46% saw increases and the rest stayed level. Globally, approximately one-third of organisations experienced funding declines in 2024. This relative stability is noteworthy, given that many think tanks worldwide struggled with funding in recent years. When asked about the past year’s funding trend, 92% of MENA think tanks said funding held steady or grew – a markedly positive outlook compared to the roughly equal mix of increases and decreases reported globally.

Such stability may be due to the prevalence of core funding and institutional support in the region. For example, no GCC think tank reported a funding decrease; most reported flat or increased funding. Additionally, none of the GCC respondents indicated reliance on foreign aid that had been recently withdrawn (e.g., the survey asked about the impact of USAID’s pullback – most in MENA said it was “not at all” affected). This insulation from international funding shocks has likely buffered Gulf think tanks.

Top Funding Channels: Consistent with the above, project grants remain essential in the MENA region but are not the sole source of funding. In the region, 69% selected competitive project grants as a top funding channel, nearly the same as the global rate of 82%. However, unrestricted core funding was a close second in MENA (chosen by 62% of respondents). By contrast, globally, only about 46% reported core funding as a major source of funding. Consulting services (paid research or advisory contracts) also play a role for some (31% in MENA), though slightly less than global (33%). Membership fees or sale of services/events are minor funding streams across the board (under 10% in MENA).

In summary, MENA think tanks enjoy more secure, core funding relative to the global average, especially in the Gulf. Government and foundation backing in GCC has led to longer funding cycles and modest growth or stability in budgets, whereas globally, many think tanks scramble for short-term project funds. This security allows MENA institutions to focus more on strategy and capacity, but also brings dependence on a few key funders (notably governments).

Insight: The overwhelmingly core-funded model in the GCC may shield think tanks from volatility, but could pose sustainability risks if a primary government backer shifts priorities. Diversifying funding sources (e.g. more private or international partners) might enhance resilience. Conversely, other regions might learn from MENA’s model of securing core support to cover overheads – a persistent challenge globally.

Staffing and human resources

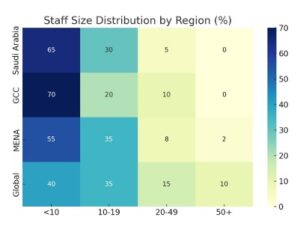

Organisational Size: Think tanks in Saudi Arabia and the GCC are generally small, with a few notable exceptions. Two-thirds of Saudi think tanks in the survey have fewer than 10 full-time staff, and none have more than 34. In the broader MENA region, approximately 77% of organisations have fewer than 20 staff members. (Globally, by contrast, 30% of think tanks employ 20 or more staff) The lean staffing in MENA reflects the relatively young and modest-sized policy research sector in many countries. However, there are outliers—2 MENA respondents (15%) reported having over 50 staff, indicating a couple of large institutions (possibly government-affiliated research centres in North Africa). Still, the median MENA think tank has 10–19 staff, like the global median category.

Staff Qualifications and Demographics: The data suggest a talent profile in transition. On average, about 30% of MENA think tank staff hold a PhD or higher, though this average hides a wide variance (some institutes reported over half of staff with doctorates, others under 10%). This regional average is slightly below the global mean (35% with PhDs), indicating a somewhat lower academic credentialing in MENA think tanks. Many institutes rely on researchers with master’s or bachelor’s degrees.

Notably, MENA think tanks have a relatively young workforce. Roughly half of the staff are under 35 years old on average. Several Saudi and GCC organisations reported large youth shares (e.g. one had 60% of staff under 35). This youth infusion could be an asset for digital adaptation and new ideas. It also reflects the growth of new think tanks in the region, often started and staffed by early-career researchers. Globally, think tank workforces skew young as well (50% under 35 on average) – MENA is on par with the world on youth representation.

Perhaps surprisingly, job stability (long-term contracts) is relatively high in MENA. Surveyed organisations reported that about 68% of their staff were on contracts of 2 years or more. In fact, the median MENA think tank had 75% of staff in long-term positions, far higher than anecdotal expectations. This likely ties back to core funding – with steady support, MENA think tanks can afford to offer secure positions. Globally, many think tanks operate project by project, often hiring on a short-term basis. The MENA data, therefore, suggest lower staff turnover and more stable teams. However, one Saudi organisation noted that only 5% of staff are long-term (likely reflecting the heavy use of short-term contracts or consultants).

Challenges in Skills and Turnover: Despite solid retention, skill gaps persist. A majority (62%) of MENA respondents “agree” or “strongly agree” that their country has a critical shortage of skilled think tank staff. Similarly, 69% indicated that staff departures pose an ongoing challenge for their organisation. Qualitative feedback suggests that competition from academia, government, or international organisations makes it difficult to attract or retain top talent. While turnover is a challenge globally, it appears that MENA managers are particularly concerned about brain drain and the limited local expertise in niche policy areas.

Hiring Plans: Encouragingly, most MENA think tanks are planning to grow their teams. Over three-quarters (77%) answered that they expect to hire additional staff in the next 12 months. In Saudi Arabia and Qatar, four out of four think tanks plan to hire or at least consider hiring. This far outpaces the global trend – worldwide, about half of think tanks plan to expand their staff post-pandemic. The growth optimism aligns with the funding stability noted earlier.

Roles in Demand: The expansion will primarily bolster research and communications roles. Among MENA organisations planning to hire, 90% are seeking researchers, and 50% will add communications staff. Far fewer are prioritising fundraising, administration, or tech roles (each 30%). Globally, research and comms are also top hiring areas (in 60% and 40% of cases, respectively). This indicates a common focus on core mission staff – analysts and outreach specialists – while support functions remain lean. The emphasis on communications expertise in half of MENA hires reflects a recognition of the need to translate research into impact more effectively (more on this in the next section). Only 3 MENA think tanks (23%) mentioned plans to hire dedicated technology/IT or AI specialists, suggesting digital transformation roles are not yet a priority in staffing.

Insight: The overall picture is of small, core-funded teams that are stable but striving to upscale skills. With secure funding, MENA think tanks can retain staff longer and plan growth, but they struggle to find seasoned experts locally. Investments in staff training and partnerships with universities could help build the talent pipeline. Additionally, introducing more formal staff development programs (e.g., fellowships, exchanges) may alleviate the perception of a skills shortage. Ensuring competitive salaries is another consideration – half of MENA think tanks cite funding constraints as a barrier to hiring top talent (mirroring global concerns).

Impact measurement and influence

Defining Impact: When asked about their most crucial impact indicator, the answers from MENA think tanks were revealing. The plurality (38%) chose media presence and citations – i.e. how often their work appears in press or is cited in public discourse. Another 23% selected social media engagement as the top indicator of impact. Only a single MENA respondent (8%) said “funding base & diversity of funders” was the key impact metric for their organisation. Interestingly, a significant number (31%) answered “Other”, specifying qualitative indicators such as policy influence or changes in legislation in the write-in field (many explicitly stated that successful policy adoption of their recommendations is the objective measure of impact).

Comparatively, at the global level, think tanks are somewhat less media-focused: about one-third prioritise media reach, and only 12% prioritise social media metrics. More global respondents (22%) than those in the MENA region consider the breadth of funding support an impact signal—perhaps viewing donor confidence as a proxy for credibility. The fact that almost one-third of respondents in every region chose “Other” indicates that the impact is often context-specific. For many, policy change and stakeholder feedback are considered more meaningful, but were not predefined options in the survey.

Policy Engagement and Outputs: The ultimate goal for think tanks – influencing policy – appears within reach for many in the MENA region. About 62% of MENA think tanks reported that they have directly contributed to a public policy decision in the past 5 years (e.g. their research was reflected in an adopted policy). Another 15% were unsure, and only 15% said they had not. This is slightly lower than the global rate (70% reporting a policy contribution) but still indicates a majority in the region have seen tangible policy wins. Saudi and GCC think tanks were among those reporting policy influence; for example, one Saudi institute provided evidence of its recommendations being incorporated into a national economic policy. These successes, however, often depend on close relationships with the government—unsurprising given many GCC think tanks are government-supported or quasi-official.

In terms of outputs produced to achieve influence, MENA organisations are prolific. 100% of surveyed MENA think tanks produce traditional research publications (policy briefs, reports) and host public or educational events. Notably, 85% create digital content, such as blogs, infographics, or podcasts, for social media dissemination – slightly above the global rate of 87%. Media engagement is also high, with about 62% of MENA think tanks regularly appearing in print or broadcast media. By providing a mix of rigorous reports, media commentary, and online content, they aim to reach both policymakers and the public.

One area where MENA lagged was in providing advisory services or consulting (46% do so, versus 59% globally). This may indicate that think tanks in the region are not yet monetising their expertise through consulting at the same level, or that governments rely on in-house units and international consultancies instead. It could also reflect capacity constraints – smaller staff may prioritise core research outputs over time-consuming consulting projects.

Transparency and Credibility: Impact is also tied to trust. MENA think tanks report mixed adoption of transparency practices. For example, around half publish financial reports or undergo independent audits, and about one-third disclose all funding sources publicly (like global averages). However, qualitative feedback suggests that many rely on their close alignment with national visions (e.g. Saudi Vision 2030) to bolster credibility, rather than formal transparency measures. This close alignment can be a double-edged sword for perceived independence.

Insight: MENA think tanks primarily equate impact with shaping narratives and policy outcomes, rather than donor growth. Their strong media orientation shows a drive to influence public discourse. Yet, measuring policy impact is tricky – many indicated that they document impact via internal records or anecdotal evidence rather than rigorous monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks. An opportunity exists to develop better impact evaluation methods (e.g. tracking specific uptake of recommendations,) which only a few institutions reported doing systematically. Additionally, boosting stakeholder feedback loops – such as obtaining formal responses from policymakers on research – could help quantify influence and refine strategies.

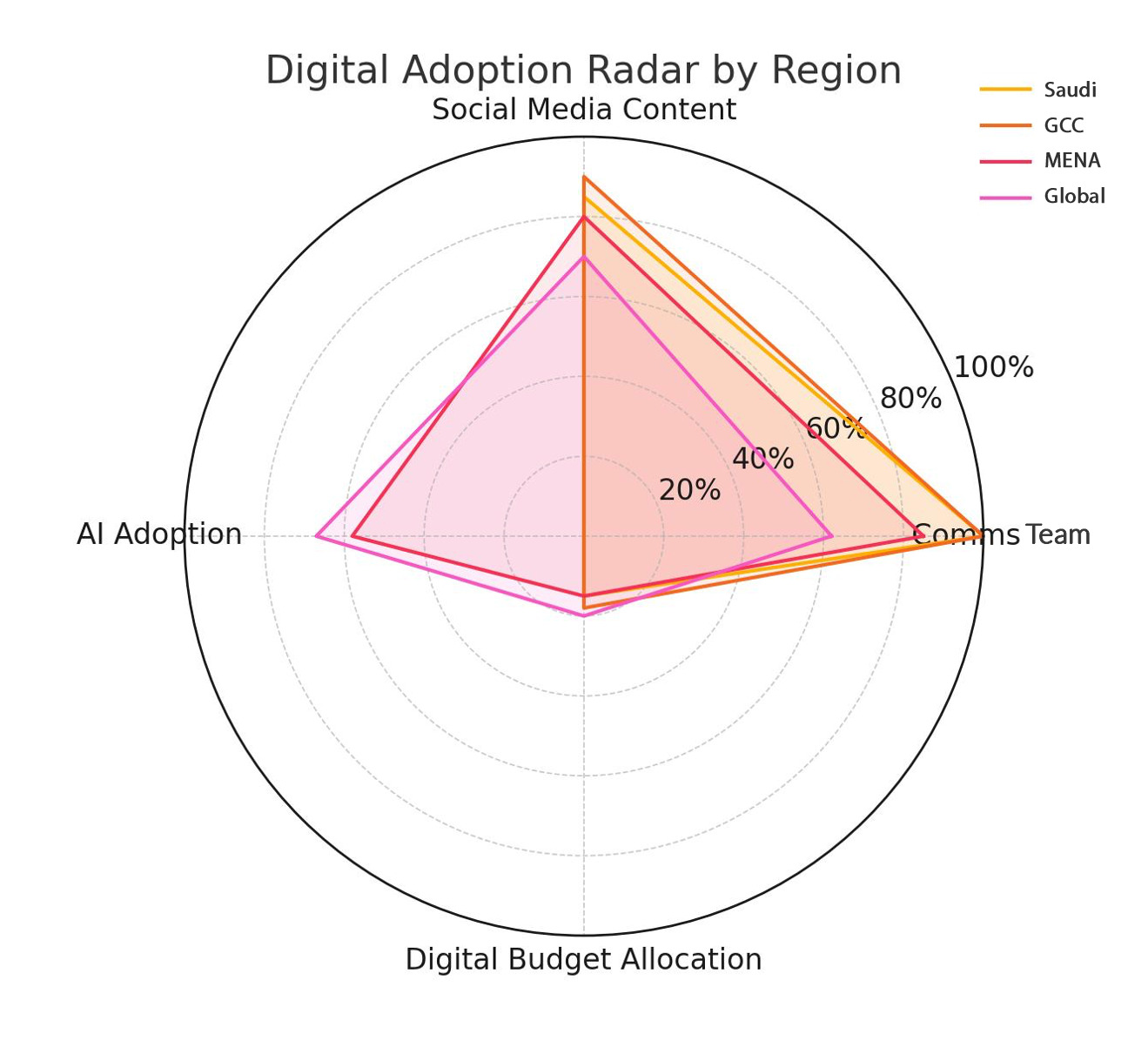

Digital strategy and innovation

Communications Capacity: A robust digital strategy is increasingly crucial for think tanks. MENA organisations appear to be aware of this—85% have a dedicated communications team or officer on staff, which is significantly higher than the 62% in the global sample who have a comms team. In fact, in the GCC, almost every think tank surveyed has a communications unit in place (many Saudi institutes have entire divisions dedicated to media and outreach). This aligns with the earlier finding that half of planned new hires are in communications roles. Moreover, MENA think tanks invest (albeit modestly) in communications: about 85% allocate up to 20% of their annual budget to communications efforts, with a median of 15%. A few outliers exist – one MENA think tank reported spending 75% of its budget on communications, which may indicate an advocacy-oriented organisation. But typically, communications spending remains relatively low, which is like global norms (where 80% of think tanks spend ≤20% on comms). Figure 2 illustrates the budget emphasis on communications, showing that the vast majority of think tanks cluster in the lower ranges (0–20% of the budget), both in the MENA region and worldwide.

Figure 2: Percentage of annual budget devoted to communications (staff and outreach). Most MENA think tanks (85%) allocate 10–20% of their budget to comms, in line with global patterns. Only one MENA respondent exceeded 50%. (Source: OTT SOS 2025 data)

Having a team is one thing; deploying digital tools is another. MENA think tanks are active on social media: as noted, 85% produce social media content regularly. Many have embraced Twitter (X), LinkedIn, and YouTube webinars to expand their reach. This paid off during the COVID-19 pandemic when online presence became essential, and it continues to be a core part of their strategy to engage younger audiences and international stakeholders.

Adoption of AI and Tech: A striking finding is the regional disparity in AI adoption. Across the global sample, about 67% of think tanks reported using some form of artificial intelligence in their work (even if just experimental). In the MENA region, adoption is slightly behind at 58% – 7 out of 12 respondents reported using AI. However, this regional figure masks a sharp split: none of the GCC think tanks are currently using AI (0 of 4), whereas most of the non-GCC MENA think tanks (e.g., in the Levant and North Africa) have begun using AI tools. In Saudi Arabia and Qatar, participants indicated they do not currently use AI, citing various barriers. In contrast, think tanks in countries such as Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt appear more willing to experiment with AI for research or communication purposes.

Why the hesitation in the Gulf? Ethical and strategic concerns were the top barriers cited by MENA respondents who are not using AI. Eighty per cent of MENA non-adopters cited “ethical concerns” (e.g., around data integrity or bias) as the reason they are deterred from adopting AI, compared to 24% globally. A few Gulf respondents also mentioned resistance to change and a lack of infrastructure. In contrast, a lack of expertise or funds was less of an issue (only one MENA institute cited insufficient expertise, compared to 35% globally). This suggests that Gulf think tanks—often closely tied to government narratives—are cautious about AI’s risks and prefer to see more global guidance or regulations before taking action. They may also feel less pressure to adopt AI immediately, given strong human resource support and access to traditional analysis tools.

Meanwhile, MENA think tanks utilising AI are applying it in select areas, primarily in research analysis (e.g., using AI for data analysis and literature review) and administrative efficiency (automating transcripts and translation). Approximately 57% of the region’s AI adopters utilise it for research tasks, 57% for administrative tasks (e.g., AI notetakers), and 57% for creating communications content. Very few use AI in fundraising or donor relations (only 14%). Standard tools include generative AI, such as ChatGPT, for writing assistance, as well as data analytics platforms. One think tank noted using AI to visualise complex datasets for policy briefs. Importantly, MENA think tanks emphasise the need for AI-related skills in ethics and data analysis. When asked which skills their staff most need for effective AI use, the top choices were “AI ethics & governance” (69% of respondents) and data analysis skills (62%).

In contrast, only 8% considered machine learning technical skills a priority for their staff. This aligns with a view of think tanks as users of AI tools rather than developers – they want staff who can critically oversee AI outputs and ensure ethical use, more than staff who can build AI algorithms. It’s a sensible approach for policy research organisations.

Digital Engagement Impact: All these efforts in communications and tech feed back into influence. There are early indications that a robust digital strategy is associated with increased visibility. For instance, MENA think tanks that reported the highest media citation counts also tended to be ones with active social media teams and who were using AI to amplify their research (as per anecdotal cross-checks of the data). One example is a UAE-based institute (not formally included in the survey but listed in the GCC list) that leverages data science and social media trend analysis to produce rapid policy insights. It has garnered a large following and attracted the attention of the government. While our sample is small, the qualitative impression is that those investing in digital capabilities – comms staff, social media, AI – are punching above their weight in shaping debates.

However, there is room for growth: even with high social media use, only 12% of global think tanks and 23% of MENA think tanks consider social media engagement their top metric for impact. Many see it as a means, not an end. The challenge ahead is converting digital reach into actual policy influence.

Insight: MENA (and especially GCC) think tanks have made strides in basic digital infrastructure – most have comms teams and produce online content. The next step is the strategic use of digital tools, such as data-driven audience targeting, interactive policy dashboards, and controlled experimentation with AI, to achieve substantive research gains. Given the cautious approach in the Gulf, a recommendation is to start with pilot projects (perhaps a limited AI experiment with clear ethical guidelines) to demonstrate value and build internal buy-in. Collaboration with tech firms or universities could help accelerate safe adoption. In summary, digital maturity in the region is growing but uneven – the foundations are in place, but the full integration of digital strategy into the think tank model is ongoing.

Conclusion and recommendations

In 2025, think tanks in Saudi Arabia, the GCC, and MENA are navigating a landscape of stable funding and enthusiastic growth, while striving to amplify their impact and adapt to new technologies. They benefit from supportive domestic funders and youthful talent, but face challenges in diversifying their support, developing skills, and embracing innovation at the same pace as their global peers. The following recommendations emerge from the findings:

- Diversify Funding and Ensure Sustainability: Gulf think tanks should broaden their funding base beyond government contracts to avoid over-reliance on a single patron. Exploring partnerships with international donors or private sector CSR initiatives can provide additional resources and resilience. Conversely, non-GCC think tanks might seek more core funding agreements (with governments or foundations) to balance the currently project-heavy portfolios. Sharing best practices in donor engagement across regions (e.g. how Latin American institutes leverage corporate philanthropy) could inspire new approaches.

- Invest in Staff Capacity Building: With hiring on the rise, it’s crucial to train and retain skilled researchers. We recommend establishing regional think tank training programs, possibly an annual “MENA Think Tank Fellows” initiative, to build skills in policy analysis, advanced research methods, and digital communications. GCC think tanks, which enjoy stable staff budgets, could lead by hosting secondments or internships for junior analysts from across the MENA region, thereby fostering skill transfer and development. Emphasising professional development (such as mentorship and attending global conferences) will also help alleviate concerns about the skills shortage and staff turnover.

- Enhance Impact Evaluation and Communication Strategies: Think tanks should articulate clearer impact frameworks. This could include defining specific policy goals and tracking progress (e.g., via policy traceability matrices or outcome journals that document where their inputs were used). Regularly publishing impact case studies will not only prove value to funders but also sharpen internal learning. In terms of communications, while nearly all are doing the basics (reports, events, social media), more could be done to tailor messages to target audiences strategically. Employing audience analytics and segmentation (e.g. crafting different messages for government, private sector, and public) can increase relevance. Given the strong media presence focus in the MENA region, training researchers in media skills and narrative writing is advised to sustain and grow that media impact.

- Cautiously Embrace Digital Innovation: The digital trajectory should continue upward. For GCC think tanks, the recommendation is to start integrating AI and advanced data tools on a trial basis. This might involve using AI for simpler tasks (summarising texts, translating content) initially, paired with strict ethical guidelines and oversight to address concerns. Meanwhile, for those already using AI in the MENA region, sharing success stories and use cases (through regional workshops or OTT platforms) could help demystify AI’s value. Additionally, all think tanks should ensure their IT infrastructure and data security are robust – a prerequisite for safe digital expansion. Finally, continue to bolster communications teams with digital storytellers and strategists, not just traditional media relations officers, to leverage new platforms fully.

In conclusion, think tanks in Saudi Arabia, the GCC, and MENA have carved out a somewhat unique position – enjoying steady support and youthful energy, which they are converting into policy influence and public engagement. To capitalise on this momentum, they should diversify partnerships, nurture their human capital, rigorously measure their impact, and innovate digitally. By doing so, they can enhance their credibility and effectiveness, both at home and on the global stage, serving as vital bridges between evidence and policy in a region undergoing rapid change.